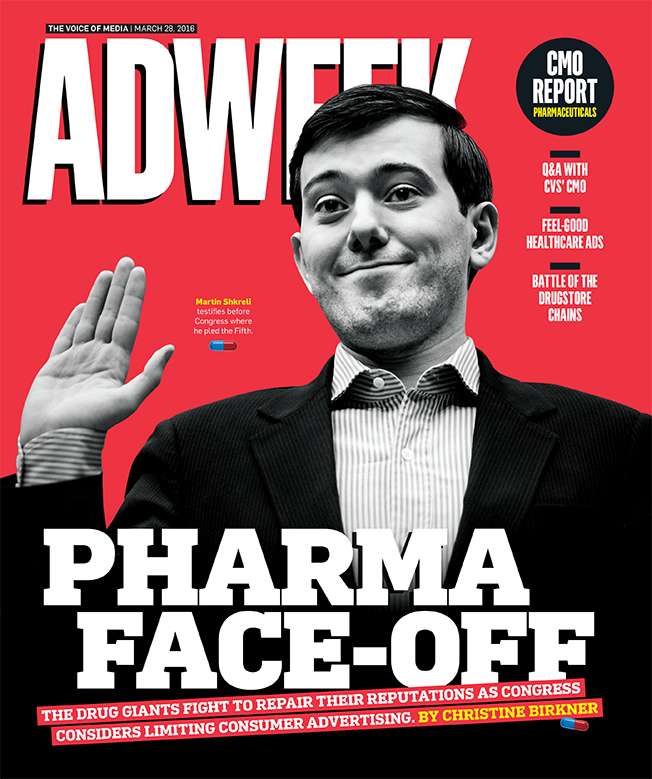

When ex-Turing Pharmaceuticals CEO Martin Shkreli smirked his way through congressional testimony in February, refusing to answer questions about how his former company increased prices for Daraprim, a drug used to treat cancer and AIDS, by 5,000 percent, it (understandably) stoked Washington's and the general public's ire against the pharmaceutical industry. That same month, Congress introduced legislation to ban direct-to-consumer (DTC) drug ads.

Not helping matters is this pugnacious election season that's drawn stark contrasts to the broader issue of healthcare. In other words, the pharmaceutical industry finds itself in deep damage control mode. Pharma's fight with Washington isn't new, but according to industry experts, the industry's efforts to restore its reputation have so far been lacking, and the battles with D.C. won't end in the near term.

"The tobacco industry and the oil industry are probably the only two industries who have worse reputations than the pharmaceutical industry," says John Mack, publisher and editor of Pharma Marketing News. "There's no advertising on TV for the tobacco industry anymore, so I could see why there are calls to ban TV advertising for prescription drugs."

Shkreli is the current poster boy for everything that's wrong with the industry, but pharma's battles with Washington date back at least to 1997, when regulatory changes by the FDA made DTC drug advertising more common in the United States. (The United States and New Zealand are the only two countries in the world that allow DTC advertising for prescription drugs, and total pharmaceutical ad spending in the U.S. rose to $4.9 billion in 2014 from $4.2 billion in 2013, according to Kantar Media.)

In 1999, the American Medical Association (AMA) released a statement that said, "Physicians must remain vigilant to assure that direct-to-consumer advertising does not promote false expectations." In November 2015, the AMA took a harder stance, calling for a ban on DTC drug advertising altogether, saying that it inflates demands for new and more expensive drugs that may not be appropriate for patients' conditions, and blaming escalating drug prices squarely on marketing and advertising costs.

Congress followed suit in February, when Rep. Rosa DeLauro (D.-Conn.) introduced a bill calling for a three-year moratorium on advertising newly approved prescription drugs directly to consumers. Back in September, presidential candidate Hillary Clinton unveiled a plan to regulate prescription drug prices that included eliminating tax breaks for consumer advertising—a proposal that the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA) said "would turn back the clock on medical innovation."

Following this year's Super Bowl, which carried a spot for irritable bowel syndrome drug Xifaxan (featuring an animated pink intestine), the FDA took aim at drug ads with animated characters, announcing it would conduct a study to determine whether such figures impact consumers' perceptions or reduce their comprehension of a drug's benefits or risks. Pharma industry experts called foul. "Marketers should be able to consider whether something is the most effective communications method. I'd hate to see aesthetic choices hampered by legislation," says Bob Brown, account services director at healthcare marketing agency Bryant Brown Healthcare.

Pharmaceutical executives and marketers also argue that DTC advertising is necessary because it educates patients about new treatment options. "The days of Marcus Welby, M.D. and Doctor Kildare are over," says Nick Colucci, CEO of Publicis Healthcare Communications Group. "Physicians being the only source of information for patients is irresponsible. The way to bring costs down is to have educated, empowered consumers, and they need information to be so."

Ultimately, it's the physicians' call on whether drugs are distributed, points out Stacey Lee, assistant professor specializing in business and health law at the Johns Hopkins Carey Business School: "While ads have resulted in patients going to their doctors and asking for more drugs and perhaps driving up the cost of brand-name drugs when there could be cheaper alternatives, at the end of the day it's still at the physicians' discretion to write the prescription or not."

Regardless, the proposed ban on DTC drug advertising isn't likely to happen, Lee says. "I don't believe the position of Congress is such that, even if Hillary [Clinton] makes it [to the presidency], there's going to be enough support for this ban to go through. If it does go through, it will only be a matter of a few days before there's a constitutional challenge to it on the grounds of corporate free speech. It's only taking center stage because of Shkreli. It's a nice time for it to get a 30-second sound bite, but when you look at the legislative and legal steps that are necessary for a ban to actually take place, I don't see it happening."

Ameet Sarpatwari, professor at Harvard Medical School who works in the division of pharmacoepidemiology and pharmacoeconomics at Brigham and Women's Hospital and studies healthcare advertising and legislation, agrees: "Even if Congress were to enact legislation restricting [DTC] advertising, it would lose in the courts under the First Amendment. So it's not going anywhere; you'll see more of it to come."

Still, DTC ads in the form of paid media could soon fade organically as social media becomes a more widely used source for patient information. "When you talk about DTC advertising, in some ways, it's kind of yesterday," says Jane Parker, CEO of InterbrandHealth. "Sixty percent of people get their first piece of health information from going online, or emailing their friends or checking social media. To say you're going to ban this kind of advertising, why go there? Because that's not where this activity is happening. It's happening in areas that the companies can't control."

"If companies get spooked by D.C., there might be a shift away from commercials. You might see more medical education, or creative digital and social efforts, to get a competitive edge," concurs Michael Roth, healthcare practice leader at Bliss Integrated. But he adds: "DTC is never going to go away. There always will be DTC in the U.S. because the proverbial toothpaste is already out of the tube. You can't just stuff it back in."

As with every other marketer, pharma brands are zeroing in on social media and digital efforts, which are more targeted and cost-effective—and could actually give pharma companies a leg up if a DTC ban ever happened, Mack says. "There are a lot of experts and consultants in the pharmaceutical industry who think that money spent on DTC advertising is wasted," he says.

Adds Colucci: "It's about making sure information is accurately targeted to the right patients at the right time. Technology gives us the best shot we've ever had at making that happen, and that will squeeze costs out of the system."

The pharma industry isn't standing pat on the issue. In 2014, PhRMA responded to D.C.'s attacks with an ad campaign, "From Hope to Cures," whose latest iteration launched in the wake of the Shkreli trial in February. The campaign, running in print, radio, digital and social channels, is designed to highlight the value that pharmaceutical innovation brings to patients' lives by telling the stories of patients and researchers. "Too often, the debate has only been about dollars and cents and ignored what these medicines actually mean to patients," says Robert Zirkelbach, PhRMA's svp of communications. "We need to make sure the public policy environment will foster what everybody agrees needs to be a focus, which is more treatments for patients."

In March, Pfizer launched a communication effort, "Before It Became a Medicine," which included print and digital ads and videos with Pfizer scientists and doctors highlighting the long research and development process (and thus, cost) involved with producing drugs that could treat diseases such as cancer, HIV and Alzheimer's. "We're telling our story of how we bring new therapies to patients and our drive to develop the cures that people and their families need. Our hope is that if more people understand what it takes to bring a new medicine to patients, then we can create a better environment for discovering treatments," says a Pfizer representative.

Pfizer's campaign makes some important points, Roth says. "Prices of drugs are made up of research and development, collecting data, hiring people, public relations, working with patient advocates, manufacturing—all of these things cost money. Marketing and advertising are part of it, but not the biggest part of it," he says.

But not everyone believes the industry has succeeded in defending the right to market directly to consumers. Rich Levy, CEO of healthcare agency Myelin Communications, says that while efforts by Pfizer and PhRMA are a step in the right direction, the pharma industry still has a lot of work to do in restoring its reputation. "The industry has done a horrible job of highlighting the benefits of pharmaceutical products, or explaining why pharmaceutical products cost what they do, so they've allowed themselves to get painted as big bad guys. The average patient is going into the pharmacy and seeing that their co-pays are going up—and they're mad. They think it's the big bad drug companies' fault. [Pharma firms] have never done a good job of saying, 'Taking that pill for your high blood pressure is protecting you from life-threatening complications.' … It doesn't help when a guy like Shkreli buys up the product and raises it by 5,000 percent overnight," he says.

(Turing Pharmaceuticals did not respond to Adweek's requests for comment. Shkreli resigned from the company in December after he was arrested on securities fraud charges for past activities at Retrophin, his former pharma firm.)

Reid Connolly, founder and CEO of Evoke Health, argues that pharmaceutical companies should highlight their patient assistant programs to bolster their reputations. "Patients and consumers tend to love pharma brands, because they are what help them, and vilify pharma companies," he says. "Pharma companies have done a lot of work to build patient assistance programs to get people who couldn't otherwise afford medication on therapy. That's a huge deal. Getting more press around those would be helpful. Like any industry, negative news sells. Martin Shkreli is in the news because he's a terrible human being. It offends me when people call him a pharmaceutical executive. He is an immoral hedge-fund manager who happened to buy a pharmaceutical company. He could be selling drywall for all he cares, as long as he can manipulate the prices. He's not in it to develop life-changing medication."

InterbrandHealth's Parker argues that pharmaceutical companies need to play up their altruistic sides, which automatically puts distance between them and characters like Shkreli. "In my mind, DTC or no DTC [advertising], the real opportunity is the relationship that you build so you become the go-to place," she says. "People go on the Mayo Clinic's website to confirm a diagnosis because the Mayo Clinic has taken the time to create an outstanding brand that they live every single day. Pharmaceutical companies have a unique opportunity to stand for very meaningful things, and I don't think they're there yet. They haven't established strong, values-based corporate brands that would withstand the occasional pot shot. They've made themselves vulnerable."

In the short term, the pharmaceutical industry will have to deal with PR flare-ups like the current one every election year, says Ed Rhoads, partner at Prophet. "Every time something like this happens, it creates more urgency in the pharmaceutical industry to improve the situation. If the hospitals and the drug providers and the federal government are all able to share better information and try to make regulating the industry a more rational process, then things will get better. Until then, the pharmaceutical industry being a political football every election year will continue forever."

Ask anyone who relies on pharmaceutical medicine, and they'll tell you this is no game.

This story first appeared in the March 28 issue of Adweek magazine. Click here to subscribe.