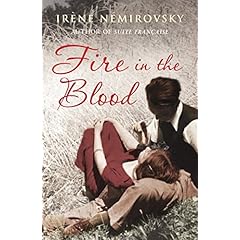

The New York Times’ Alan Riding uses the upcoming publication of another previously undiscovered novel by Irene Nemirovsky to discuss just how much impact she’s had on readers worldwide – about 65 years after her death in Auschwitz. After the much-dissected success of SUITE FRANCAISE comes CHALEUR DU SANG (or FIRE IN THE BLOOD), which was discovered in handwritten format amidst archived papers in 2005. Originally conceived as early as 1937, Nemirovsky wrote the 150-page volume around the same time as she wrote the beginnings of SUITE FRANCAISE. Unlike the latter work, BLOOD (which Knopf will publish here on September 25) is more in the vein of Jane Austen and unconcerned with the effects of war.

The New York Times’ Alan Riding uses the upcoming publication of another previously undiscovered novel by Irene Nemirovsky to discuss just how much impact she’s had on readers worldwide – about 65 years after her death in Auschwitz. After the much-dissected success of SUITE FRANCAISE comes CHALEUR DU SANG (or FIRE IN THE BLOOD), which was discovered in handwritten format amidst archived papers in 2005. Originally conceived as early as 1937, Nemirovsky wrote the 150-page volume around the same time as she wrote the beginnings of SUITE FRANCAISE. Unlike the latter work, BLOOD (which Knopf will publish here on September 25) is more in the vein of Jane Austen and unconcerned with the effects of war.

Riding also touches on the newfound controversy accompanying the release of DAVID GOLDER, Nemirovsky’s second novel originally published in 1928. Critics have noted that the book portrays a wealthy and embittered Jewish immigrant to Paris, that in the 1930s Némirovsky wrote short stories for some right-wing journals and that in 1940 she and her family converted to Catholicism (although this did not save her or her husband). “Her supposed ‘self-hating’ has been more of an issue in the Anglo-Saxon world and Israel than here,” said Olivier Rubinstein, president of Editions Denoel. “When Denise [Epstein, Nemirovsky’s surviving daughter] and I went to Israel for the publication of SUITE FRANCAISE in Hebrew, there were virulent debates about her supposed anti-Semitism. I am not trying to hide aspects that are disagreeable,” he went on, “but I think the question is more complex. I think it was less anti-Semitism than the disdain that bourgeois Jews like Nemirovsky had for immigrant shtetl Jews from Poland and Russia. And remember, we’re judging actions of 1938 with the post-Holocaust eyes of 2007.”

To which I say, right on, having picked up a copy of DAVID GOLDER earlier this week only to devour it in one sitting, agog at its depiction of the quest for wealth turned sickeningly awry. The novel deserves all the debate and discussion for it can sometimes be an uncomfortable read, but it is no less brilliant for such ambiguities. After all, Nemirovsky had no idea at the age of 26 what her fate would be a little more than a decade later. She was, in her own way, writing what she knew, doing so with care and humanity and compassion for her characters, no matter how odious they could be. I hope Vintage has plans to publish the book here as soon as possible.