What’s on the Other Side of the Uncanny Valley?

How will people and machines coexist as the latter become more like the former?

It all started with a laugh—Alexa's laugh. And suddenly, we remembered the gadgets in our homes are not connected to a woman with a headset in a cubicle in Tampa, but rather a virtual entity that has no human form and may or may not be taking its first stabs at free will.

It sounds like the plot of a B-list horror movie—your loyal virtual assistant suddenly breaks free and turns on you, laughing as you’re trapped within a tiny cylinder and forced to forecast the weather, play Cardi B and order paper towels until you die.

Amazon said it is “evaluating options to make [the laugh] even less likely,” but the fact remains that machines are becoming more human. And they’re not going to stop. There are already robot receptionists, robot patients that can express pain and a robot dog that can open doors.

It already seems like we’re on the verge of an apocalypse—if climate change doesn’t get us, nuclear war will.

So I have some good news and some bad news.

The bad: We need to add robots to the list.

The good: We need to start thinking about how to infuse the best parts of humanity into technology—or stop development altogether—or we really are doomed.

Part I: The Robot Future

Upon The Jetson’s 50th anniversary in 2012, Paleofuture blogger Matt Novak, then of Smithsonian Magazine, called the show “the single most important piece of 20th century futurism” because in part it packaged inventions like jetpacks, flying cars and robot maids into accessible 25-minute segments.

The original run lasted only a single season, possibly because it was the first-ever program to be broadcast in color on ABC, but most households had black-and-white televisions in 1962 and missed the full spectacle. It was revived in 1985, however, and Rosey the robot maid—the Jetson family’s humanlike helper Novak called “perhaps the most iconic futuristic character to ever grace the small screen”—was given a more prominent role.

For at least 50 years, we have dreamed of cohabitating with robots like Rosey as some kind of futuristic ideal. But as we take our first tentative steps toward that reality, we find ourselves in what is known as the uncanny valley—a limbo of sorts in which human and machine aren't always readily distinguishable—and, frankly, things get weird as we interact with increasingly human machines. But, as we forge bravely ahead, we will actively shape our future with robots, and whether we end up with a friendly, collaborative, wise-cracking Rosey or a Skynet hell-bent on killing us will be determined by our actions moving forward.

A 2011 story in Time attributed our continued lack of home robots to practical issues like intelligence (not enough of it), materials (too cold and hard to be inviting) and cost (too much).

Masahiro Mori

Masahiro Mori

“No one wants the Terminator walking around their kitchen,” Time noted, positing the future is more likely to include a number of simple, inexpensive robots that perform different household tasks. Tech company iRobot’s vacuuming robot Roomba, which debuted in 2002 and has since sold more than 18 million units, is a good example.

But, seven years later, robot price tags remain a big hurdle, and the landscape is still muddled.

A review from CES 2018 of the robot Aeolus called it the ideal home robot—it can vacuum, mop, put away dishes and move furniture—but noted the price is equivalent to a family trip overseas. (Aeolus did not respond to a request for clarification.)

And that’s one reason the robot business is a tough gig.

In October 2017, Jibo, a $900 robot that can provide weather forecasts, sports scores and trivia, made its debut, calling itself “your new best friend.” Reviews likened the 6-pound, 11-inch robot to “Alexa and a puppy inside one adorable robot.” But by July 2018, news emerged Jibo had laid off employees as it awaited additional funding or an exit. Jibo did not respond to a request for comment.

In August 2018, robotics and AI company Anki announced its own personable home robot called Vector. It doesn’t do housework, but, like voice assistants, Vector can provide answers to factual questions and queries about the weather as well as set timers and play blackjack. Anki, however, is clear it’s Vector’s personality that sets it apart.

In a blog post, Anki president Hanns Tappeiner wrote, “In addition to cutting-edge tech, we’ve equipped Vector with a friendly, life-like personality because we believe the future of robots is more than just the best technology. The future of accessible home robots hinges on [emotional quotient (EQ)] as much as IQ.”

Anki announced a Kickstarter campaign on Aug. 8, and, in the end, nearly 8,300 backers pledged $1.9 million, which is nearly quadruple its goal. (It is on sale now for $249, or about the price of an Echo Show, $100 more than Google's new Home Hub. But, to be fair, Echo and Home don't have eyeballs.)

Meanwhile, Amazon is reportedly working on its own home robots code called Vesta in its R&D unit Lab126. It’s not clear what the robot will do, but Bloomberg said it might be like a mobile Alexa and that Amazon wants these domestic robots in employees' homes by the end of the year. Amazon declined comment.

Alphabet and Huawei are also reportedly developing home robots. Huawei did not respond to a request for comment, but a spokesperson for X, a division of Google focused on “moonshots,” said in a statement the company is optimistic robotics and machine learning can solve some of humanity’s problems and it is exploring a range of ways to do so. But she did not comment on home robots specifically.

“Really good technology is technology you don’t notice that blends seamlessly into the fabric of your life,” said Jason Snyder, global CTO at production network Craft. “Right now, with robotics, so much is really clunky.”

That means existing products still require human intervention, which Snyder said will decrease over time. But consumers will also have to figure out what kind of a relationship they want with robots and how much permission they want to give technology to do their bidding.

In the meantime, Snyder said, we’ll probably start with multiple in-home robots before evolving to something more unified.

Part II: Genesis

A robot is a machine that can perform one or more actions automatically. Examples of robots we’re already familiar with include car washes, ATMs and remote control cars.

AI, on the other hand, is the ability to exhibit humanlike intelligence. This is what makes it possible for machines like robots to learn and perform more tasks typically done by humans. Alexa, Google Assistant and other voice-enabled assistants are good examples of mainstream AI. And this is really where the in-home robot trend envisioned in 1962 begins.

Nearly 50 million U.S. adults have welcomed smart speakers into their homes already, according to a study from news site Voicebot.ai, voice application development firm PullString and Rain Agency.

Market research firm Juniper Research says nearly 3 billion voice assistants will be in use globally across all platforms—including smartphones, wearables, connected cars, smart speakers and PCs—by the end of 2018, and it expects a 28.1 percent average growth rate each year until 2022. Smart speakers will make up 63 million of those devices and will grow at an annual rate of 51.2 percent over that time.

And this is despite behavior that sometimes makes consumers uncomfortable. Such was the case when Google announced Duplex, a technology for conducting what it called "natural conversations to carry out real world tasks over the phone," like booking a haircut or a restaurant reservation, because it sounds so much like a person. This gave rise to something like the robotic equivalent of informed consent: After some backlash following its debut, Google Assistant now identifies itself when performing actions on behalf of users.

But Google wants its assistant to be as human as possible.

Cathy Pearl, head of conversation design outreach at Google, noted in order for assistants to be successful, they need to follow standard conventions of human-to-human conversations, such as being clear what the question is, what the user can say and when it’s the user’s turn to speak.

And, Pearl said, a voice that sounds too synthetic is more difficult for people to process and can lead to confusion.

“For example, if the intonation for a question is incorrect (such as the emphasis being on the wrong word), it adds to a user’s cognitive load, making the task more burdensome,” she said. “It’s a bit like listening to someone who has an unfamiliar accent—you can still understand them, but it takes more concentration and there’s more room for misunderstandings.”

Sophie Kleber, global executive creative director of product and innovation at digital agency Huge, agreed people want machines that are more human than robotic but also noted we’re at a strange point at which we have let these quasi human assistants into our lives and sometimes forget they are machines, at least until they start behaving erratically.

“The most beautiful thing about [Alexa’s laugh] is it reminded us they are machines in a stark way,” Kleber said. “But really this is a wakeup call—they are not sentient things and not built around serving us. They are really machines that are way dumber than we make them out to be. There’s a funny thing in our personalities called [empathy]—even if an innate object exhibits some reminders of human traits and we know it is not human, our mind tends to still assign human qualities to it.”

And, Kleber said, when machines talk, people naturally assume a relationship.

“Assistants are designed this way,” she said. “If you dive into their personalities, they all follow certain rules of human interactions or exploitations around flattery, obedience and even the fact that they are funny is a deliberate design.”

Researchers in the department of social psychology at the University of Duisburg-Essen in Germany demonstrated this increasingly complicated relationship in an experiment with Softbank Robotics’ humanoid robot Nao. In the study, 85 subjects interacted with the robot. All were told to turn off the robot at the end, but, for about half of the participants, the robot said, "No! Please do not turn me off! I am afraid of the dark!” As a result, 13 of 43 people refused to turn Nao off, and 30 took twice as long to turn it off as the group who heard no such complaints. Study leader Nicole Krämer said in a statement that this is because when robots act like humans, “you [cannot] help but treat them like humans because of our innate social behavior."

Part III: Blurring Lines

It’s unlikely we’d ever mistake Rosey, Aelous, Jibo, Vector or a mobile Alexa for a human being. But outside this niche of domestic robots, efforts are underway to marry humanity and AI in other ways that get even more confusing.

Take virtual influencers like Shudu Gram and Miquela Sousa, for example. Some say realistic digital models like this could be the Christie Brinkley and Claudia Schiffer of the future because they don’t argue, eat or get tired.

And then there’s Ava, a Tinder user who turned out to be a bot promoting the sci-fi movie Ex Machina, but not before toying with those who matched with her.

AI chatbot Replika, which learns about users as they chat and adapts accordingly, is another case study of the man-machine relationship. It is the brainchild of Eugenia Kuyda, founder of messenger company Luka, whose best friend died in 2015. She fed thousands of his text messages into a neural network so a bot could learn his speech patterns and she could talk to him again. Now, the reported 2.5 million people who use Replika can essentially do the same thing, but with themselves.

“The idea [is] to create a personal AI that would help you express and witness yourself by offering a helpful conversation,” the company says on its website. “It’s a space where you can safely share your thoughts, feelings, beliefs, experiences, memories, dreams—your ‘private perceptual world.’”

But replacing people, fooling them or reincarnating them is where it gets dicey.

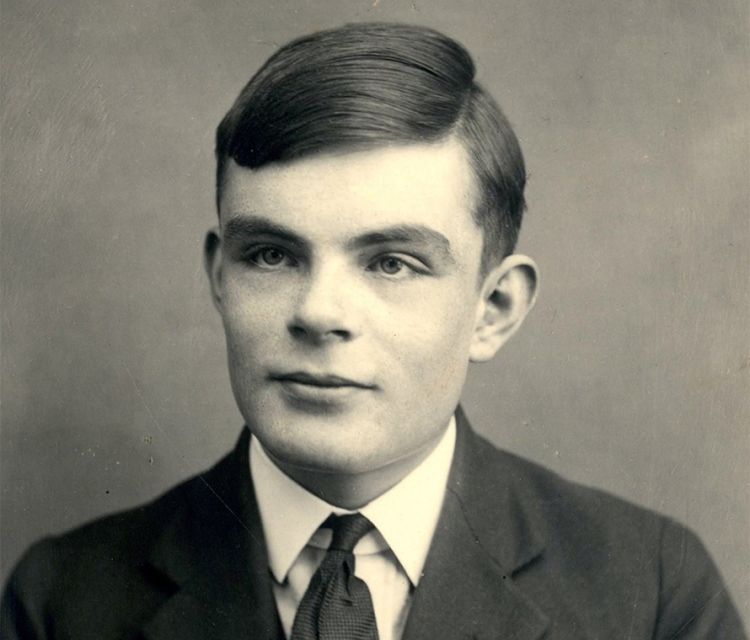

Alan Turing

Alan Turing

Per Joey Camire, principal at brand design consultancy Sylvain Labs, users are apprehensive about being manipulated by voice assistants, which perhaps arises from a history of academics trying to prove the value of their robot creations by fooling people in order to pass the Turing Test, the assessment that determines whether a machine exhibits intelligent behavior indistinguishable from that of a human. And the fear among people is they won’t be able to distinguish between what’s real and unreal.

Which brings us back to the uncanny valley.

Tokyo Tech Professor Emeritus Masahiro Mori first posited the theory of the uncanny valley in 1970. In an essay, Mori said our affinity with robots increases as they become more human, but only until they become human enough to temporarily confuse us as to what they are—the uncanny notion something is not, in fact, human. At that point, our affinity drops into the eponymous valley.

Using a prosthetic limb as an example, Mori said, "When we realize the hand, which at first sight looked real, is in fact artificial, we experience an eerie sensation. For example, we could be startled during a handshake by its limp boneless grip together with its texture and coldness. When this happens, we lose our sense of affinity and the hand becomes uncanny."

And, Mori’s theory goes, when robots become indistinguishable from humans, our affinity with them picks up again.

Part IV: Redefining Our Relationship

After a honeymoon phase in which we were enamored with these devices, Kleber said we’re moving on to the next step, which will include defining the boundaries and delineating what we do and don’t want more clearly.

We’ll also have to clearly define what it means to be human and what it means to have machines assist us. Per Snyder, this includes issues like whether people can marry machines and whether machines can be CEOs of companies, as well as whether we want machines to fight wars for us or farm for us.

And that maybe means adding a branch of government to focus on machines—or including it in trade associations like the 4A's.

“We need to agree on what this is going to be,” he said.

And no matter what robots look like on the outside, they, like Replika, will start to look like us on the inside as they learn about us and adapt accordingly.

“I think it’ll look like who it’s talking to,” Snyder said. “If you’re into death metal, it’ll be into death metal, if you’re into Holly Hobbie, it’ll look like Holly Hobbie, if you’re into the New York Giants, it’ll be into the Giants.”

Clyde McKendrick, chief innovation officer at consumer behavior consultancy Canvas8, agreed one of the next steps will include social connectivity in which users start to feel the machine understands them.

He also said there’s an opportunity to design the future of tech so the machine understands and adjusts to human emotions. That includes deciphering a user’s vocal intonations and whether they are asking for something because they are happy, sad, jealous or mad and what its reaction should be. This is related to the concept known as sentience, which is the ability to feel.

Microsoft’s Tay, the chatbot Twitter users quickly made racist, misogynistic and anti-Semitic, should perhaps give us pause for thought here.

The ability of machines to mirror and amplify both good and bad ideas is why AI should be included in corporate social responsibility, Snyder said.

“I don’t see a lot of politicians using machine learning and AI as a platform—there are other social issues that need to get sorted out first, but it’s really just as important in my mind because [AI] can take basic social issues and amplify them and manipulate understanding at scale,” Snyder said.

He said self-driving cars are a good example.

“Why those crashes happen is not because the machines are naughty or want to hurt people—it’s a number of factors,” Snyder added. “Machines are literal, engineering is literal. We need to be really clear and maybe part of it is legislation and part of it is also around self-governance. People who own stock in corporations need to ask these questions. As shareholders, they need to understand these significant issues in the same way they responded to toxic waste or recycling. It’s social responsibility.”

Machines will also increasingly get smarter—to the point they may become smarter than we are. That point is known as singularity.

“The super intelligence that creates is like when the universe becomes knowledge—everything talks to everything else,” Snyder said. “In a universe where everything is alive and interconnected, it’s almost a religious thing in a way.”

In a blog post, Ben Goertzel, chief executive of SingularityNet, a decentralized marketplace for AI algorithms that seeks to distribute the power of AI, said SingularityNet’s blockchain-based AI network allows different AI agents using different algorithms to make requests and share information. And, as they collaborate, Goertzel said it can become an “overall cognitive economy of minds” with intelligence beyond individual agents.

“This is a modern blockchain-based realization of AI pioneer Marvin Minsky’s idea of intelligence as a 'society of mind,'” he added.

In fact, Hanson Robotics, which works with SingularityNet, says founder David Hanson seeks to “create genius machines that will surpass human intelligence.” Its lifelike robot Sophia taps into multiple AI modules to see, hear and respond with empathy.

But how exactly—or when—this will shake out is unclear.

Snyder said we’ll get to a point where AI is as smart as people—possibly within ten years, but definitely within 20—and we’ll probably get to a point where AI is smarter. (Goertzel’s estimate for this point of artificial general intelligence [AGI] is perhaps even as soon as five to ten years.)

“We have never had anything smarter than people as far as we know,” Snyder said. “What will that world be like? Once that happens, many people believe it will accelerate at a rapid pace and what will become of humanity? What it means to be human changes when our biology and our technology merge together and then start to move out into the universe.”

And, theoretically, this is where robot overlords could come in.

“I think the moment we achieve AI at parity with human intelligence we will embrace it. Once AI exceeds human intelligence it will grow at an exponentially fast rate. This is where all the theories kick in,” Snyder said. “My opinion is that right now there’s millions of little organisms crawling around on our skin, on our desks, our bedsheets, curtains, vegetables, etc. I reckon AI will regard us as we do those entities.”

But the good news is we have the power now to shape what robots will become. (The bad news is we had the power to shape what the Internet became, too.)

In his post, Goertzel said AGI doesn’t require a body, but if we want AGI with human-like cognition—and that can understand and relate to people—it “needs to have a sense of the peculiar mix of cognition, emotion, socialization, perception and movement that characterizes human reality,” which means it needs a body “that at least vaguely resembles the human body.”

Goertzel said part of his motivation in creating SingularityNet is to use AI and blockchain in an open marketplace in which anyone can use the world’s most powerful AI for any purpose.

“Put simply: I would rather have a benevolent, loving AI become superintelligent than a killer military robot, an advertising engine or an AI hedge fund,” he said. “If an AGI emerges from a participatory ‘economy of minds’ of this nature, it is more likely to have an ethical and inclusive mindset coming out of the gate.”

According to Hanson Robotics, Hanson wants these three human traits integrated into AI: Creativity, empathy and compassion.

As a result, Hanson says genius machines “can evolve to solve world problems too complex for humans to solve themselves.”

“One conclusion I have come to via my work on AI and robotics is: if we want our AGIs to absorb and understand human culture and values, the best approach will be to embed these AGIs in shared social and emotional contexts with people,” Goertzel added. “I feel we are doing the right thing in our work with Sophia at Hanson Robotics; in recent experiments, we used Sophia as a meditation guide.”

In September, SingularityU The Netherlands—which includes the Dutch alumni of a global community using technology to tackle the world’s biggest challenges—hosted an event about technology and compassion with the Dalai Lama.

His take: “There is real possibility to create a happier world, peaceful world. So now we need vision. A peaceful world on the basis of a sense of oneness of humanity.”